The artist and muse, the electric spark for high art, and in the case of Paris Red — high literature. This novel is artistic, poetic, exotic, and reflects deep care to reach perfection of prose, multi-dimensional characters and stimulating scenes. It’s as if this book was polished by a brunisseue, a “silver burnisher”, and their bloodstone, achieving a gleaming finish. It is an intense and bold story set in 1862 Paris of a young working-class woman, Victorine Meurent, who honors her internal pulse, despite the unknown and risks as she enters the world of wealthy painter Édouard Manet. This is a novel of discovery and an exploration of what drives and binds the muse and artist. Paris Red is like no other art-based historical novel I’ve read, it stirred not often accessed emotions and bodily drives, it is juicy in a way I could never have imagined nor expected. The story delves into brazen human and artistic hungers, but also lays bare an empowered female in protagonist Victorine, an adolescent coming into her own.The inquiry into the artist’s vision and how one sees and views the world and comes to understand what art means to oneself spoke deeply to me.

The artist and muse, the electric spark for high art, and in the case of Paris Red — high literature. This novel is artistic, poetic, exotic, and reflects deep care to reach perfection of prose, multi-dimensional characters and stimulating scenes. It’s as if this book was polished by a brunisseue, a “silver burnisher”, and their bloodstone, achieving a gleaming finish. It is an intense and bold story set in 1862 Paris of a young working-class woman, Victorine Meurent, who honors her internal pulse, despite the unknown and risks as she enters the world of wealthy painter Édouard Manet. This is a novel of discovery and an exploration of what drives and binds the muse and artist. Paris Red is like no other art-based historical novel I’ve read, it stirred not often accessed emotions and bodily drives, it is juicy in a way I could never have imagined nor expected. The story delves into brazen human and artistic hungers, but also lays bare an empowered female in protagonist Victorine, an adolescent coming into her own.The inquiry into the artist’s vision and how one sees and views the world and comes to understand what art means to oneself spoke deeply to me.

Drop the cloak, assume a pose on the divan, expose your essence, you feast, he devours and see if he and she can capture and reveal each others souls…

Stephanie Renee dos Santos: What special challenges did you encounter to embody your protagonist, the artistic seventeen year old Victorine Meurent and the escapades she and her dear friend Denise find themselves exploring after meeting painter Édouard Manet?

Maureen Gibbon: When you’re young, you share so much with your best friend; the two of you really count on each other. I wanted to bring the closeness of female friendship to Paris Red. Before my fictional version of Victorine meets Manet, she is sharing a room with her best friend Denise in order to make ends meet, but also because the two are a great team. They are their own little family.

The day Victorine meets Manet, Denise is with her, so Manet meets both of them. He’s intrigued by the two young women, and by their intense friendship. That’s something I drew from my own experience in order to portray.

In 1983 when I was twenty years old, I studied and traveled in Europe. One day in Venice, a friend and I met an older man on the street, and we began to spend time with him. We walked the quiet city for hours, talking, laughing and teasing. There was a kiss on the street.

I never forgot the tension of our triangle, or the sensuousness of those summer walks in the dark. All of that went into Paris Red—along with plenty of research about how young working class women made their way in Paris in the nineteenth century. In many ways, their lives were not so different than the lives of young women today: they had to earn a living, they worried about unwanted pregnancies, and they craved independence.

Fiction is like that for me. I borrow anything I need for the sake of the story, and I blend research, memory and imagination. And I hope the result is an intoxicating mix for the reader.

SRDS: What compelled you to include art and artist in your historical novel?

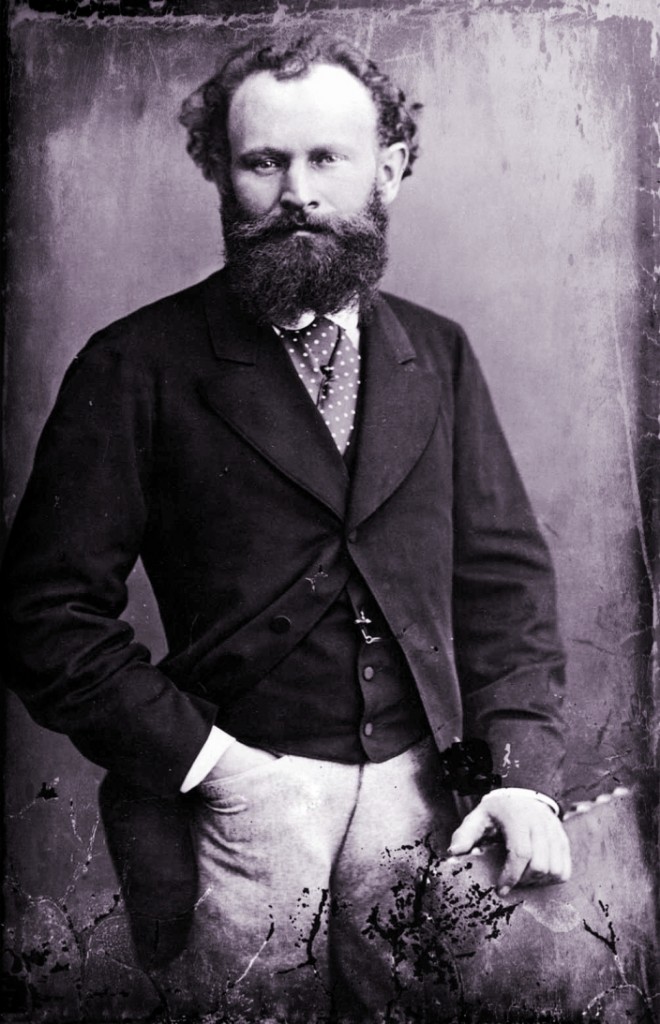

MG: Édouard Manet’s Olympia was the starting place for the novel. I always had strong feelings about the nude in the painting, even before I knew anything about Victorine Meurent. After I read Eunice Lipton’s Alias Olympia and learned a little about Victorine’s life, I could not stop thinking about her. Victorine was a working class girl, just seventeen when she met Manet – but her story did not end with Manet. She became an artist, too, and that alone is astounding because she didn’t have resources. But she still found a way to make art, and she even exhibited in a Salon where Manet exhibited. She survived Manet by forty-four years, living into the 20th century

SRDS: What drew you to your specific visual art medium, artwork, and/or artist?

MG: As I learned more about Victorine Meurent, I learned more and more about Manet and his work, and I fell deeply in love with both people. Manet had to break away from the lessons he was taught in order to come to his own style of painting. He began something so new and provocative with Olympia that he infuriated people, and they were vicious in their attacks on him. And still he went on painting.

So the initial draw for me was a single painting, but after I got just a little way into the research, these two specific people, artist and model, kept me involved. I love and revere both Manet and Victorine as individuals. I admire the way they lived their lives.

SRDS: What unique historical objects and/or documents inspired the story?

MG: In addition to Manet’s paintings, I relied on Charles Marville’s photographs of Paris, as well as detailed maps of Paris in the 1860s. I was also moved by the erotic photographs of Félix-Jacques Antoine Moulin, and a collection of photographs compiled by Dr. George Henry Fox, a dermatologist who studied syphilis in the late 19th century.

SRDS: Is there an art history message you’ve tried to highlight within the novel?

MG: The relationship between artist and muse is a two-way street.

In the past I felt uncomfortable with the word “muse,” but I’ve come to my own understanding about it as a result of writing Paris Red. From my own experience as a writer, I know I cannot wait to be inspired by an outside source in order to do my work – sometimes it’s work itself, writing my way into something, that brings about “inspiration.” But there are sources and practices I turn to in order to keep myself in touch with my own creativity, or with a story, and I think those sources and practices might be viewed as muse-like.

But if we really are talking about an artist inspired by a particular person, as Manet was so clearly inspired by Victorine Meurent, I think it’s essential to see that relationship as active. Whatever transpired between Manet and Victorine in his studio was profound and took on a life of it’s own; it’s why he was able to push through into a new style of painting. I don’t think that kind of energy could have happened if Victorine had been a passive figure or inert body. She was active and involved.

SRDS: What do you think readers can gain by reading stories with art tie-ins?

MG: My book would not exist without an art tie-in. I think people are tremendously interested in creativity, in where paintings and poems come from. Books that discuss the creative process are compelling to many people – and not just people interested in the arts. I loved The Imitation Game because I think it depicted how a creative mind works. Alan Turing created a computer and not a painting, but the machine came from the wellspring of his creativity, and from his utter focus. When we’re creative, we tap into something that is us and is also larger than we are, and I think people are fascinated by that, by the multitudes we all contain.

SRDS: What fascinating information did you uncover while researching but were unable to incorporate into the book, but can share here?

MG: Manet went on painting almost until his death. He worked on small canvases of flowers up until about a month before he died. I learned this from The Last Flowers of Manet, by Robert Gordon and Andrew Forge, with translations by Richard Howard. Manet created art as long as he could. He is my hero.

SRDS: Any further thoughts on art in fiction you’d like to expand on?

MG: I’ve been in this love affair with Manet and Victorine for more than a decade. Paris Red enriched my life personally and artistically. I don’t know who I might have become without this book in my life, without Manet’s art, without his and Victorine’s story.

SRDS: Are you working on a new historical novel with an art tie-in? If so, will you share a little with us about your next release?

MG: I have three new projects going, and one of them has a tie-in to a film. In some ways, it also addresses the role of the muse. I hesitate to say more because I don’t want to jinx myself. I believe in doing the thing and not talking about it until it’s done.

About the author: Paris Red is Maureen Gibbon’s third novel. It will be published in the U.S. by W. W. Norton in April 2015. Christian Bourgois, Éditeur published the French translation, Rouge Paris, in October 2014.

About the author: Paris Red is Maureen Gibbon’s third novel. It will be published in the U.S. by W. W. Norton in April 2015. Christian Bourgois, Éditeur published the French translation, Rouge Paris, in October 2014.

Gibbon is also the author of the novels Swimming Sweet Arrow and Thief, which have been published internationally, and the prose poem collection Magdalena.

Her short fiction, nonfiction, and book reviews have appeared in The New York Times, The Daily Mail, Minneapolis Star Tribune, Playboy, Byliner, The Huffington Post and other publications.

A graduate of Barnard College and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, Gibbon was awarded a Bush Foundation Artist Fellowship in 2001, and Loft McKnight Artists Fellowships in 1992 and 1999. In 2006, she received a Mill Foundation Artist Residency at the Santa Fe Arts Institute.She lives in northern Minnesota.

For more about Maureen’s works: http://www.maureengibbon.com/

To buy (debut’s April 20th!): Paris Red

Join us here April 11th for an interview with M.J. Rose, acclaimed author of The Witch of Painted Sorrows!

Interview posting schedule:

2014: August 30th Susan Vreeland, Lisette’s List (new release), September 27th Anne Girard, Madame Picasso (new release),October 25th Yves Fey, Floats the Dark Shadow, November 29th Mary F. Burns, The Spoils of Avalon (new release), December 27th Kelly Jones, The Woman Who Heard Color

2015: January 31st Heather Webb, Rodin’s Lover (new release), February 28th Alyson Richman, The Mask Carver’s Son, March 28th Maureen Gibbon, Paris Red (new release), April 11th M.J Rose, The Witch of Painted Sorrows (new release), April 25th Lisa Brukitt, The Memory of Scent, May 30th Lisa Barr, Fugitive Colors, June 27th Lynn Cullen, The Creation of Eve, July 25th Andromeda Romano-Lax, The Detour, August 29th Frederick Andresen,The Lady with an Ostrich Feather Fan, September 26 Nancy Bilyeau, The Tapestry (new release), October 31st Laura Morelli The Gondola Maker

Join Facebook group “Love of Arts in Fiction”!

For more on Paris Red, visit Sarah Johnson’s blog review at “Reading the Past”.