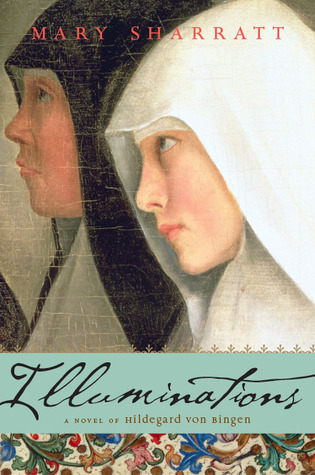

I’ ll put this simply: I loved Mary’s novel ILLUMINATIONS. Loved it, loved it. A spellbinding chronicle of the life of the German Benedictine abbess, writer, composer, philosopher, mystic, visionary, and polymath Hildegard von Bingen (1098–1179). I adored the subject matter, the story line, the characterizations, the settings, the writing, the pacing, the scenes: everything. I highly recommend this novel. It is my wish for the world to read it. Compelled, I nearly read it in one sitting, only exhausted eyes and that fact it was 4:00 am forced me to put it down, and I even played hooky from my own novel project the next day to finish it. Awed, I contacted Mary Sharratt, the author of five other acclaimed books, to let her know how much I loved and valued her work and to see if she would be open to give an interview.

I’ ll put this simply: I loved Mary’s novel ILLUMINATIONS. Loved it, loved it. A spellbinding chronicle of the life of the German Benedictine abbess, writer, composer, philosopher, mystic, visionary, and polymath Hildegard von Bingen (1098–1179). I adored the subject matter, the story line, the characterizations, the settings, the writing, the pacing, the scenes: everything. I highly recommend this novel. It is my wish for the world to read it. Compelled, I nearly read it in one sitting, only exhausted eyes and that fact it was 4:00 am forced me to put it down, and I even played hooky from my own novel project the next day to finish it. Awed, I contacted Mary Sharratt, the author of five other acclaimed books, to let her know how much I loved and valued her work and to see if she would be open to give an interview.

Thank you Mary…

Q: Will you please tell us about your inspiration for the novel ILLUMINATION?

For twelve years I lived in Germany where Hildegard has long been enshrined as a cultural icon, admired by both secular and spiritual people. In her homeland, Hildegard’s cult as a “popular” saint long predates her official canonization in May 2012. I was particularly struck by the pathos of her story. The youngest of ten children, Hildegard was offered to the Church at the age of eight. She reported having luminous visions since earliest childhood, so perhaps her parents didn’t know what else to do with her.

According to Guibert of Gembloux’s Vita Sanctae Hildegardis, she was bricked into an anchorage with her mentor, the fourteen-year-old Jutta von Sponheim, and possibly one other young girl. Guibert describes the anchorage in the bleakest terms, using words like “mausoleum” and “prison,” and writes how these girls died to the world to be buried with Christ. As an adult, Hildegard strongly condemned the practice of offering child oblates to monastic life, but as a child she had absolutely no say in the matter.

The anchorage was situated in Disibodenberg, a community of monks. What must it have been like to be among a tiny minority of young girls surrounded by adult men? Disibodenberg Monastery is now in ruins and it’s impossible to say precisely where the anchorage was, but the suggested location if two suffocatingly narrow rooms built on to the back of the church. Hildegard spent thirty years interred in her prison, her release only coming with Jutta’s death.

What amazed me was how she was able to liberate herself and her sisters from such appalling conditions. At the age of forty-two, she underwent a dramatic transformation, from a life of silence and submission to answering the divine call to speak and write about her visions she had kept secret all those years. In the 12th century, it was a radical thing for a nun to set quill to paper and write about weighty theological matters. Her abbot panicked and had her examined for heresy. Yet miraculously this “poor weak figure of a woman,” as Hildegard called herself, triumphed against all odds to become one of the greatest voices of her age.

Q: And about the research that went into writing the novel?

I read everything about Hildegard I could get my hands on, in both English and German. Unfortunately I don’t read Medieval Latin! But I read the original sources in translation, from her voluminous letters to here works of visionary theology to her book Physica, dealing with healing, medicine, and the natural world, as well as many secondary sources. While writing, I listened obsessively to her ethereal music. I also went on a research tour to all the Hildegard sites along the Rhine.

You can read about it in my blog: http://marysharratt.blogspot.co.uk/2009/07/research-trip-to-bingen-germany.html

Q: Is the character “Richardis” based on a real historical person?

Hildegard’s beloved protegee, the nun Richardis von Stade, was a real historical person. Her mother, also named Richardis, was a wealthy aristocratic widow who was instrumental in providing the funding to allow Hildegard to found her abbey at Rupertsberg. Her daughter, Sister Richardis, is mentioned in Hildegard’s Scivias, her first book of visionary theology.

Hildegard says she would not have been able to write about her visions without Richardis’s support. Hildegard also revealed a very human side of herself in the passionate protest letters she wrote to her archbishop, Richardis’s mother, and Richardis herself when Richardis wanted to leave Rupertsberg to take the position of abbess at a Benedictine house in northern Germany. Later she deeply regretted leaving Hildegard, as her brother’s letter to Hildegard revealed. Later she deeply regretted leaving Hildegard, as her brother’s letter to Hildegard revealed.

Q: What parts of the novel were the most difficult to write? And why?

I found it quite intimidating to write about such a religious woman. In the end, I found I had to let Hildegard breathe and reveal herself as human. The passages about Hildegard as a child walled into the anchorage were particularly hard for me to write. I felt claustrophobic as I was writing these scenes and had to follow each writing session with outdoor exercise in nature, something young Hildegard herself would have been forbidden.

Q: Do you feel you grew or changed spiritually from writing this novel?

It definitely made me see my birth religion of Catholicism in a new light.

While writing this book, I kept coming up against the injustice of how women, who are often more devout than men, are condemned to stand at the margins of established religion, even in the 21st century. Women priests and bishops still cause controversy in the Episcopalian Church while the previous Catholic pope, John Paul II, called a moratorium even on the discussion of women priests. Modern women have the choice to wash their hands of organized religion altogether. But Hildegard didn’t even get to choose whether to enter monastic life—she was thrust into an anchorage at the age of eight. The Church of her day could not have been more patriarchal and repressive to women.

Yet her visions moved her to create a faith that was immanent and life-affirming, that can inspire us today. The cornerstone of Hildegard’s spirituality was Viriditas, or greening power, her revelation of the animating life force manifest in the natural world that infuses all creation with moisture and vitality. To her, the divine was manifest in every leaf and blade of grass. Just as a ray of sunlight is the sun, Hildegard believed that a flower or a stone was God, though not the whole of God. Creation revealed the face of the invisible creator. Hildegard’s re-visioning of religion celebrated women and nature and even perceived God as feminine, as Mother. Her vision of the universe was an egg in the womb of God. Hildegard shows how visionary women might transform the most male-dominated faith traditions from within.

Q: What interesting tidbits were you unable to put into the novel, but could share here?

Hildegard’s life was so long and eventful, so filled with drama and conflict, tragedy and ecstasy, that it proved mightily difficult to squeeze the essence of her story into a manageable novel. My original draft was forty-thousand words longer than the current book. I cut out two major subplots.

One involved Hildegard’s relationship with the young apostate and escaped monk, Maximus, whose burial in her churchyard triggered the interdict that left Hildegard and her daughters excommunicated. The other subplot, based on historical fact, was Hildegard’s exorcism of and subsequent friendship with a Cathar woman named Sigewize. Officially only priests were allowed to perform exorcisms, but the monks of Brauweiler Abbey near Cologne didn’t know what to do with this crazy Cathar woman who said that the demons would only leave her body if “Old Schrumpligard” told them to. So the monks dutifully sent Sigewize to the now elderly Hildegard.Hildegard was skeptical about possession and believed that most supposedly possessed people were actually epileptic. But she performed the ceremony, after which Sigewize seemed to experienced a deep peace of mind. Sigewize then became a sister at Rupertsberg.

Q: Can you share with us what you are working on now?

The Dark Lady’s Masque, my new novel in progress, reveals the star-crossed love affair between William Shakespeare and his Dark Lady, Aemilia Bassano Lanier, the first professional woman poet in Renaissance England.

Again, thank you Mary for this exquisite and insightful interview! And please visit Mary’s blog “Viriditas”.

Buy this page-turning novel!