Firstly, what is a “figura de convite“?

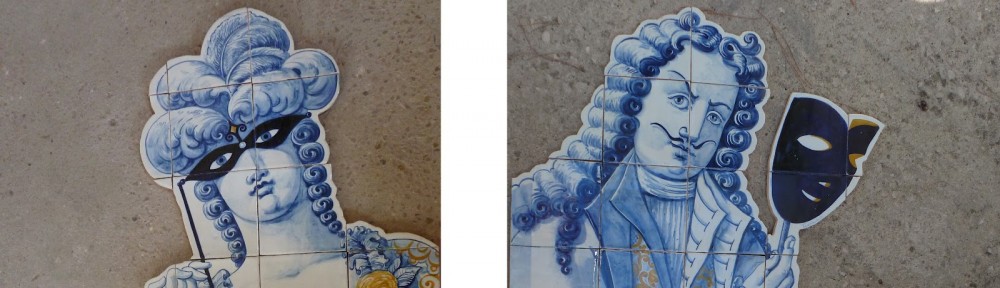

A figura de convite is an invitation figure made of *azulejos, tiles. They’re life-sized tile cut-out images of a finely dressed nobleman or lady, halberdiers or a footman that were affixed to walls at the entrances of palaces, on stair-landings, and patios to welcome visitors during the eighteenth century in Portugal and Brazil.

* “Azulejo” is the Portuguese term for a glazed tile. The word comes from Arabic الزليج “al zulaycha” meaning little polished stone, and is not to be confused with “azul”, blue, which it is often mistaken. It is true that there are many blue azulejos, and that can explain the confusion, but, historically, the first glazed tiles that appeared on the Iberian peninsula, brought by the Muslim Moors in the thirteenth century, were glazed in mainly hunters green, burnt sienna, and mustard yellow.

The figura de convite appeared in Portugal around the year of 1720. The innovation was the first time in the history of tile fabrication that the medium deviated from the square composition and embraced the outline of the cut-out, thus opening up a new world of tile designs. Its creation is attributed to the master tile maker who went by the monogram PMP, and whose life story has been lost to history.There’s speculation that possibly the artist’s initials were those of Padre Manuel Pereira, a clergyman and patron to a large tile making workshop (shop name unknown) in Lisbon. His disciples are thought to have produced tiles for palaces and churches all over Portugal and Brazil. But there is no exacting evidence and secure proof that he really is or was the famous monogram PMP…it’s a mystery of art history.

The figura de convite appeared in Portugal around the year of 1720. The innovation was the first time in the history of tile fabrication that the medium deviated from the square composition and embraced the outline of the cut-out, thus opening up a new world of tile designs. Its creation is attributed to the master tile maker who went by the monogram PMP, and whose life story has been lost to history.There’s speculation that possibly the artist’s initials were those of Padre Manuel Pereira, a clergyman and patron to a large tile making workshop (shop name unknown) in Lisbon. His disciples are thought to have produced tiles for palaces and churches all over Portugal and Brazil. But there is no exacting evidence and secure proof that he really is or was the famous monogram PMP…it’s a mystery of art history.

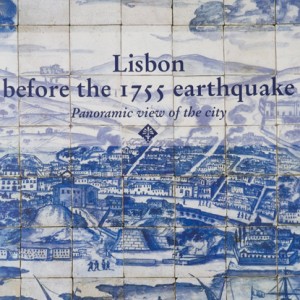

During the first part of the eighteenth century and up until “The Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755″, Portugal was at the pinnacle of its wealth and extravagance, arguably the richest European country during this time period, and all due to the gold and precious gem extraction from its colony, Brazil, and the slave trade from Africa.

Around the year of 1730, yellow detail work began appearing in the figures, mimicking the use of gold thread being used in cloth embroidery work, demonstrating the vast amounts of gold coming into Portugal from Brazil. It was also around this time that the powdered wig hairstyles of the figures began to visibly shift to a less showy display, recording the period’s shifting tastes.

Innovations of the figura de convite was ongoing with figures like this Roman centurion (left) and rare musical duo with a wiry dog (right).

Words of greeting were sometimes incorporated into the compositions, like this fellow whose beckoning: “Come in your Lordship”. The art form of tile making flourished in Portugal during the eighteenth century with the country’s peerless affluence, and produced one of the greatest world-wide advancements in tile making: the figura de convite.

Two “mock” book jacket ideas for CUT FROM THE EARTH (despite the fact I hope to be traditionally published and have the publisher’s art department work out a fantastic book jacket!)

The figura de convite is one of the artwork highlights in my forthcoming art-based historical novel Cut From the Earth, a story of Portuguese tile and its surprising makers — The Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755 — and the wisdom of nature to guide heal.