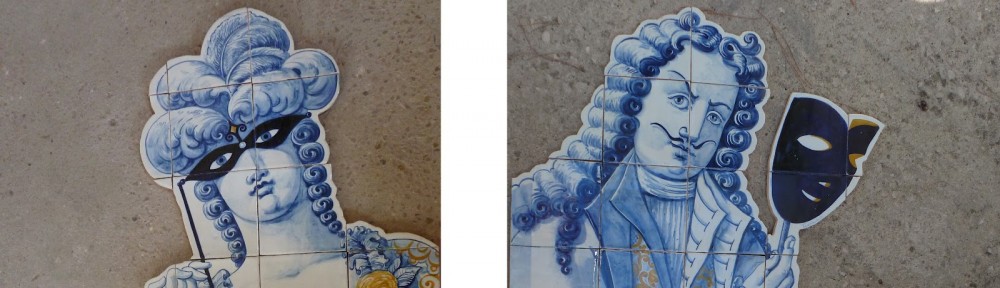

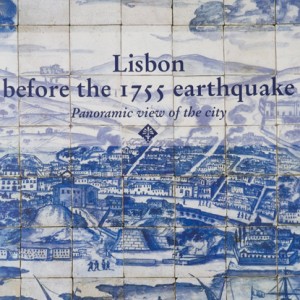

The Royal Ribeira Palace prior to the 1755 Great Lisbon Earthquake as seen in the 23 meter long blue and white tile mural that survived the quake.

What was lost?

In the Year of Our Lord 1755 on November 1st, All Saints Day, Portugal the “Queen of the Seas'” capital, Lisbon, was devastated by an estimated 9.0 Richter scale earthquake, what is referred to today as “The Great Lisbon Earthquake”. At this time, the arts flourished in Lisbon with the country’s peerless affluence as exemplified in extensive public and private tile works throughout the city and outlying areas. And as was glorified in the recently completed ostentatious Phoenix Opera House with its grand wooden cupola, of which all was but destroyed in the earthquake and the subsequent tsunami waves and mass fire that followed.The Royal Ribeira Palace along the Tagus river (now the modern day square of Terreiro do Paço) housed a  magnificent library of 70,000 books, the royal residence also harbored hundreds of works of art: ancient manuscripts, sculptures, tapestries, and paintings by Titian, Ruben, and Correggio — all were lost.The royal archives disappeared, together with detailed historical records of explorations by Vasco da Gama and other early navigators’ charts and maps, plus works by Emperor Charles V, Hebrew bibles, and other treasures brought back from The New World, Asia and Africa by Portugal’s explorers. Only twelve of the seventy-two convents of the city were spared, along with their priceless relics. All the city’s hospitals with their medicinal knowledge and thirty-three palaces within the city with vast art caches were destroyed.

magnificent library of 70,000 books, the royal residence also harbored hundreds of works of art: ancient manuscripts, sculptures, tapestries, and paintings by Titian, Ruben, and Correggio — all were lost.The royal archives disappeared, together with detailed historical records of explorations by Vasco da Gama and other early navigators’ charts and maps, plus works by Emperor Charles V, Hebrew bibles, and other treasures brought back from The New World, Asia and Africa by Portugal’s explorers. Only twelve of the seventy-two convents of the city were spared, along with their priceless relics. All the city’s hospitals with their medicinal knowledge and thirty-three palaces within the city with vast art caches were destroyed.

After three centuries as one of Europe’s most vibrant, opulent and prosperous capitals during the Age of Discovery, Lisbon was almost completely leveled in a single day, along with its extensive tributes to the arts and collections.The material loss was astronomic for Portugal and its foreign traders: the British, the French, the Spanish, the Netherlands, Germany, Ireland, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland. It is estimated the losses to foreign investors equaled approximately twelve million pounds sterling, of which, more than half represented British losses.

Many thought it was the wrath of God that had struck the “Princess of a City” — Lisbon — due to the excesses and riches and lavish lifestyles many indulged in and flagrantly enjoyed in the face of the Lord, His precepts, and the Inquisition. While those involved in the flourishing ideas of the Enlightenment in the north of Europe sought other reasons to explain the disastrous events. Lisbon was reduced to rubble with an estimated 70,000 to 100,000 left dead and saw the end of the city’s Golden Age, but also the birth of a new, more forward thinking municipality that would rise up from the ruins.

What was inspired?

Never in European history had a natural disaster received such international attention, as Lisbon’s losses had no precedent in Europe. And it was because of the advent of newspapers and news pamphlets across the continent and outlying areas that news spread quickly of the disasters. Plus, Lisbon had one of the most important European ports for trade with the Americas, Asia and Africa, so word rippled swiftly out by sea and reached far and wide. Artist and writers alike swooped upon Lisbon to record and report on the catastrophes.

German engravers immortalized the before and after depictions of Lisbon with ink on paper with works like The Ruined Capital of the Imperial Portuguese, The collapse of Lisbon and the fires that followed on November 1 st of 1755, and Homeless, helpless, maimed and executed criminals forced to public camps by J.A. Steislinger.

While Holland’s etchers recreated the scene of The Tsunami as produced by Vinkeles and F. Bohn.

The French sent their own lithographers to depict and record the destruction.

The French sent their own lithographers to depict and record the destruction.

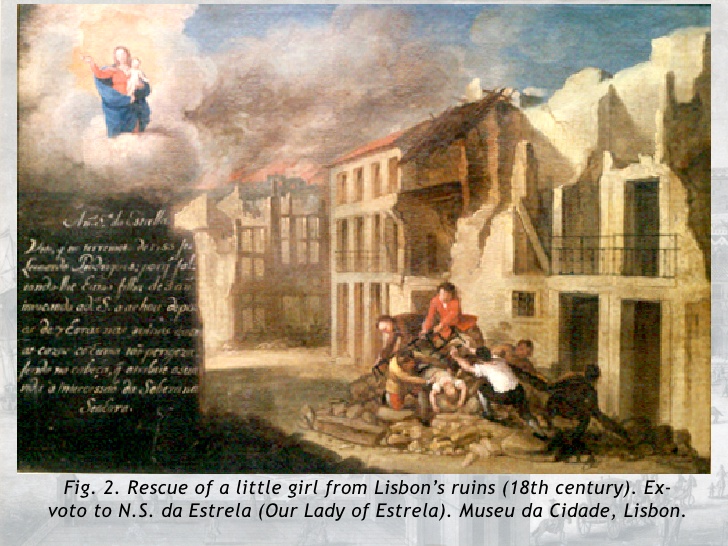

And for years to come paintings, engravings, and ex-voto works dedicated to saints, along with tile works were made recalling and remembering the tragic events of All Saints Day, November 1, 1755.

And for years to come paintings, engravings, and ex-voto works dedicated to saints, along with tile works were made recalling and remembering the tragic events of All Saints Day, November 1, 1755.

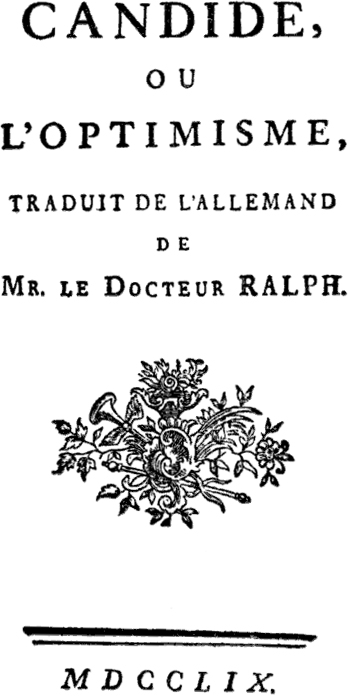

Philosophers of the Enlightenment such as Voltaire, Kant and Rousseau were inspired by the tragic events and wrote works influenced by it. Voltaire’s novel Candide, Ou l’Optimimse (1759)  and his poem Poème sur le désastre de Lisbonne (“Poem on the Lisbon disaster”) directly observed and commented on the events. Whereas Immanuel Kant furthered and elevated the concept of the sublime, although in existence prior to 1755, by attempting to comprehend the enormity of Lisbon’s tragedies. Kant published three separate texts on the Lisbon earthquake, after collecting and investigating news pamphlets which were in large circulation about the events as he worked on formulating a theory as to the causes of the earthquakes. According to Walter Benjamin, Kant’s early book on the earthquake: “..probably represents the beginnings of scientific geography in Germany. And certainly the beginnings of seismology.” Jean-Jacques Rousseau was also influenced by the devastation, he believed the severity of the events was due to too many people living within close quarters of the city. Rousseau used the earthquake as an argument against large cities, as part of his desire for a return to a more naturalistic way of life.

and his poem Poème sur le désastre de Lisbonne (“Poem on the Lisbon disaster”) directly observed and commented on the events. Whereas Immanuel Kant furthered and elevated the concept of the sublime, although in existence prior to 1755, by attempting to comprehend the enormity of Lisbon’s tragedies. Kant published three separate texts on the Lisbon earthquake, after collecting and investigating news pamphlets which were in large circulation about the events as he worked on formulating a theory as to the causes of the earthquakes. According to Walter Benjamin, Kant’s early book on the earthquake: “..probably represents the beginnings of scientific geography in Germany. And certainly the beginnings of seismology.” Jean-Jacques Rousseau was also influenced by the devastation, he believed the severity of the events was due to too many people living within close quarters of the city. Rousseau used the earthquake as an argument against large cities, as part of his desire for a return to a more naturalistic way of life.

Innovative seismic architecture was developed after the earthquake to rebuild Lisbon as lead by King José I’s Prime Minister, Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, Count of Oeiras, later named Marques of Pombal. Pombal is famous for saying: “What now? We bury the dead and heal the living.” and “The cultivation of literary pursuits forms the basis of all sciences, and in their perfection consist the reputation and prosperity of kingdoms.”

The installment of large-scale prefabricated buildings was developed, along with a new style of tile work named Pomblinos which were characteristically fast and economical to make.

Pombal envisioned a progressive enlightened capital as opposed to the Lisbon of the past which was a city shackled by dogma and dominated by archaic Catholic orthodoxy that shunned science. From the ashes of Lisbon, Pombal created a new state-of-the-art capital with modern sanitation, wide streets and strict building codes. He saw this was a singular opportunity for renewal and advancement of Lisbon, a capital that could become a model for the rest of Europe. For it was the first time standardized prefabricated buildings were used on such a grand scale, and ones built with quake-resistant elasticity. Later, the avant-garde town planning was emulated in Paris, France by Baron Haussmann and in Barcelona, Spain by Ildefons Cerdà. Churches were rebuilt with more hardwoods and gold from colonial Brazil and re-embellished with monumental gold gilding, all lavished in the rich Portuguese Baroque style, reviving a new “Golden Age” as exemplified in the São Roque and Santa Catarina churches.

The renewal and transformation of Lisbon was a prodigious feat, one carried out by the determined, visionary, and at times consider ruthless Pombal. Today a statue of the Marques de Pombal stands at the top of a monument in the main roundabout at the top of Avenida da Liberdade looking down on the new rebuilt downtown center, a lion at his feet, a symbol of strength of not just survival but of progress arisen from destruction.This history, plus more, and its people are given flesh, bone, heart and voice in my forthcoming novel: Cut From the Earth.