A few days before leaving for Peru, in 2006, to paint plants, my travel partner informed me I would be traveling solo. Disillusioned, alone on a flight from Seattle, Washington, into Lima I read in its entirety Inés of My Soul by Isabel Allende. Above the cloud line I soared south as a clear defining moment, mid-book, took place — I want to do this, write stories like this — for the book, its characters and subject matter captured and entranced me. A calling crystallized: to write historical fiction. To give voice to the voiceless. To tell stories of those that have gone unheard, which often times are the tales of heroic women, minorities, and animals.

With this epiphany I landed in Peru.

My first night there I was awakened by a fistfight as two drunks pummeled each other against MY DOOR. I fled Lima. And I headed for the jungle town of Pullcalpa situated along the Ucayali River in the Peruvian Amazon. I was in search of the environmental painter and Ayahuasca shaman Don Pablo Amaringo, as I was painting endangered, medicinal, and exotic plant species of the Americas, and I wanted to meet and talk with this profound painter and teacher. I found him, in his mid-80’s with his guitar playing older brother, age 88, in the noisy motorcycle tuk-tuk riddled town. It was an ethereal experience, listening to his brother play guitar, while Don Pablo Amaringo showed me his astonishing works and explained them; all painted in bright colored acrylics of mystical jungle scenes that appeared to him while in the embraces of the two vines that make up the hallucinogenic Ayahuasca drink.

After this soulful encounter I headed north by transport ship up the Ucayali River, in search of plants to paint. The boat’s top deck was laden with supplies for the river villages and I convinced the crew to allow me to pitch my tent amongst the goods. Their only requirement was that I not get up and walk around at night. I agreed to this, which meant forfeiting access to the head, but I knew I could resort to a mountaineering trick — peeing in a water bottle in the dark of my tent, luckily, I had two with me.

Later that night I found out why I could not walk around at night.

Gunfire.

A series of shots exploded off the sides of the vessel; I watched tracers of white light streak across the nylon walls of my tent. Lying flat upon my Thermarest, I came to the conclusion and assumption that the crew was fighting off raiders wanting to board, for what I presumed had to do with drugs. Cocaine. Petrified I stayed in my thin walled cocoon, eventually peeing in my open-mouthed water bottle.

Then in the last hours of darkness there was a rustling at my tent door. Fear, then anger grew inside me, the only thing on my mind: rape. Someone continued to aggressively shake at my tent’s zipper door, and I unzipped it slowly, readying myself to meet my aggressor.

“You need to pay for your boleto,” the ticket collector said. God I thought is that it! You’re not going to try and rape me! In the dark of the early morning, happy this man was not going to try to physically assault me, I thought: “Damn, but do I really need to pay for my passage at this crazy hour?”. I produced the money. He left. But sleeping was now impossible. So began my four-day float up the Ucayali — my next stop — the jungle locked town of Iquitos, Peru.

I spent my hours aboard ship spying into the jungle landscape and watching the voluminous boiling water — verdirness on all side — until we arrived at Iquitos’s red clay mired bank and the captain drove the flat bottom boat up the mud, wedging it between a fleet of already-beached cargo and passenger boats, all like pigs at the trough. Again, I was greeted by the noisy Indian imported tuk-tuk motorcycles, and I longed for the sounds of the forest, and to start painting. I needed a guide. With three other jungle seekers and now found guide, we boarded an outboard boat loaded with five days of supplies, and motored to the mouth of a small tributary, bunking up for the night at a local’s palm roofed hut. The next day we paddled a dugout canoe up a narrow waterway clogged with lime-green water hyacinths and dangling vines that over hung the channel’s edges.

I sketched as we traveled.

The heat stifling, I struggled to draw until we reached, late in the day, a light bulb shaped water opening where we made camp on high ground. At day’s end, we swam in the center of the blub-shaped inlet, weary of the crocodile. Slowly, the truths of the place began to be revealed. Our guide explained to us that here, where we were camped were some of the last remnants of primary rain forest just off the main waterways of the Ucayali and Amazon; as for centuries Europe and now other countries have been extracting the once seemingly unlimited hardwoods from this place. It then dawned on me, that all the forest I had seen coming up the Ucayali those four days was second growth forest.

On Christmas Day, the forest was alive; as we back-tracked the slue; ten pairs of yellow and blue macaws, tiny black and golden monkeys, and a sloth, saw us out of the primary jungle. A magnificent Christmas present.

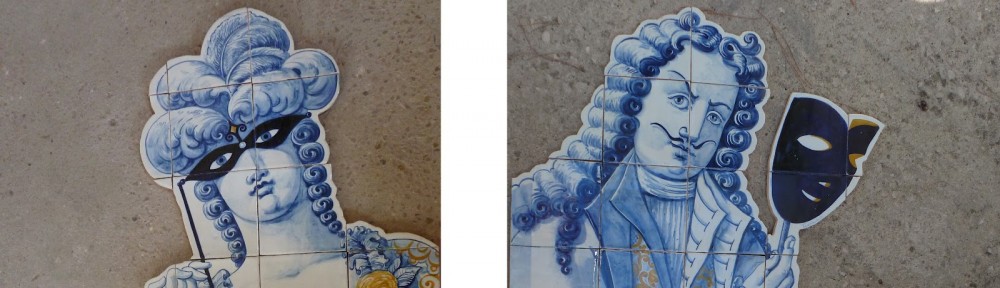

Back in Iquitos, alone again, I took lunch along the riverside malecón, boardwalk. As I walked I noticed the decaying, but beautiful, tile work that adorned the facades of the buildings. And I asked myself: Why is this tile work here in the middle of the jungle? How did it get here? Thinking, this is something one would see in Spain or Portugal.

A torrential rain fell as I ate and pondered these questions, water running down the two steps, a small falls that cascaded into the subterranean eatery, housed in an old tiled mansion. I then realized the gorgeous dark hardwoods in the churches of Europe, black jacarandá wood pews and altars — that wood came from here, the Amazon. Tiles were imported into the jungle for the rich European wood exporters to display their wealth; an exchange of one natural beauty for a man made one. It is from this realization and my continued curiosity that the creation of Cut From The Earth was sparked. And what I found in my investigating was a story far greater and more tragic than I had known, with the stories of many voices begging to be told.

Cut From The Earth is born of the love of azulejos, specifically Portuguese tile, and the awe inspiring Amazon — whose tales, wonders, and tragedies are as endless as its waterways.

Wow! I love this!